On the Lake – an introduction January 29, 2010

Lessons from the Lake (or, Thoreau on Ice) February 19, 2010

Snow Days (Three Degrees of Separation) March 5, 2010

The Last of Fahnestock April 2, 2010

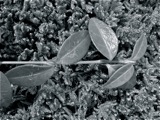

Spring, Closely April 9, 2010

The Signs to Holmes (the comet story) May 28, 2010

Zipping at Hunter: a reminder of joy June 30, 2010

Hallowed Lands October 8 2010

Nature's Fingerprints November 26, 2010

Spinning Out February 11, 2011

That Thai Trip (Thai Elephant 2 restaurant review) March 2011

Over My Head in Cabarete Bay: a near-life story May 2011

Lightning Strikes - the fire out on main street June 2011

9/11: Images and the Aftermath September 2011

Dylan and 9/11: Going Back to New York City October 2011

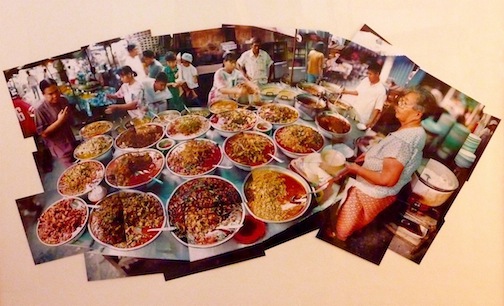

That Thai Trip

The events that altered my destiny took place in an old wooden house on the outskirts of Seattle. This was the 80s, back before

Starbucks

and grunge. Friends drove me out to small operation off a

frontage road by the railroad tracks. It looked seedy to me, but

inside was nicely lit and comfortable. I had never tried

this before, but I had done Indian in London, so I knew I could handle

the heat. The bowl I tasted that night was an epiphany.

Starbucks

and grunge. Friends drove me out to small operation off a

frontage road by the railroad tracks. It looked seedy to me, but

inside was nicely lit and comfortable. I had never tried

this before, but I had done Indian in London, so I knew I could handle

the heat. The bowl I tasted that night was an epiphany. It’s no exaggeration to say that Gaeng Kieu Wan Gai, green curry chicken from Thailand, changed my life.

I had no idea that food could be transcendent. I never imagined that the dynamics of flavor and spice, color and texture—coconut milk and chili peppers, fish sauce and lemon grass--could be experienced as beauty. It was transporting, complex and intriguing, a synesthesia of tastes and smells and color. That mouthful was a gateway, a window on a world I couldn’t imagine. I felt an unerring pull to its aesthetic.

The next 8 years I took four long trips to Southeast Asia, backpacking and then working as a freelance writer and photographer. I was searching for that taste, and the culture it implied: a space for magnificence and beauty in the commonplace and everyday; the relaxed Buddhist heart that so contrasted with my buzzing Western brain. You feel it the minute you land, beating even amidst the sweat and madness of Bangkok. These are not the smiles of salesmen.

I've had French food in Paris and fine wines I wasn't paying for, but this was on another level. Travelling in Thailand is the only place I've felt that reincarnation is real. I seemed to learn the language very quickly and used it without my usual nervousness; I know my way around. With the first step, and before I set foot in a restaurant, I am immersed in the street food of KrungTep, the City of Angels: the grilled chicken and papaya salad, and the new epiphany of fresh tropical fruit, papaya, watermelon and pineapple served with lime and a dash of chili. The food of paradise was everywhere and it was cheap.

During my travelling years I searched out Thai restaurants worldwide, chewing lemon grass while eschewing local cuisine from Havana to Vienna. You find the best Thai food in Ma-and-Pa places where you’d never expect it...like Phoenix. Now that I’ve settled, I cook it once a week for my kids, to whom I’ve passed the gene. My son Joe is the only kid at Pawling Elementary who brings in full-blast green curry in his SpongeBob lunchbox.

Which is the long way round of saying that I know Thai food.

My career in newspaper journalism started here, and has now come full circle. The first article I wrote for the first issue of the New York Press (Russ Smith, editor) was a restaurant review of a place in Queens called Jaiya, which for the record I didn't like much. I was already by then a bit of a Thai snob, having travelled, and Jaiya appeared to be, like a lot of the restaurants in Bangkok, run by Chinese, not Thai. Two strikes against it--it was too much like Chinese food. Despite my words back then, Jaiya is still out there, with branches in Manhattan and Long Island.

Perhaps the single thing we miss most having moved up here from the

city is being able to pick up the phone to order food from any Asian

land delivered to our door. Every time we see a new restaurant

opening in the area, we are hoping against hope that it isn’t another

Italian. We have nothing against Italian, or pizza per se, but it

is Variety, and not just oregano, that is the spice of life.

Perhaps the single thing we miss most having moved up here from the

city is being able to pick up the phone to order food from any Asian

land delivered to our door. Every time we see a new restaurant

opening in the area, we are hoping against hope that it isn’t another

Italian. We have nothing against Italian, or pizza per se, but it

is Variety, and not just oregano, that is the spice of life.Magically, a very good Thai restaurant has opened nearby on Route 22 in Patterson, where the Steak House used to be. It’s called Thai Elephant 2, and is affiliated with the well-loved original Thai Elephant in Astoria, Queens. The Harlem Valley continues to challenge my cynicism in ways I never imagined. (Don’t worry, I’ll always have the school board.)

By way of a review, I will just say the food is good and so are the prices. We went for dinner the first Friday they were open and they were overwhelmed. People were grumbling about how long the food was taking, but everyone shut up once it arrived. A few days later they had staffed up and everything went smoothly. Weekends you should still prepare to be patient. Buddhas are there to help you.

For me, the best Thai food is comfort food, more basic than fancy. Novice or not, you can’t go wrong with the standards. All Thai restaurants should be able to make these well, and Thai Elephant does: Green Curry Chicken or Red Curry, Beef Salad, Squid Salad, Shrimp Soup and Chicken Coconut Soup. Start there, then experiment. Get extra rice. The curries should be eaten over rice, and the soups and salads can be. Mix more in if it gets too spicy. Beer tastes great with Thai, adds excellently to the hot-chili buzz, and you can bring your own until they get their licence.

Thai Elephant 2, 2693 Route 22 in Patterson, is open seven days a week for lunch and dinner. (845) 319-6295.

Spinning Out

We are accustomed to hear this king described as a rude and boisterous tyrant; but with the gentleness of a lover he adorns the tresses of Summer.

--Thoreau, on Winter

I didn’t get hurt and couldn’t even find a scratch on the car, so in terms of drama, it’s not really much. Just another snow story.

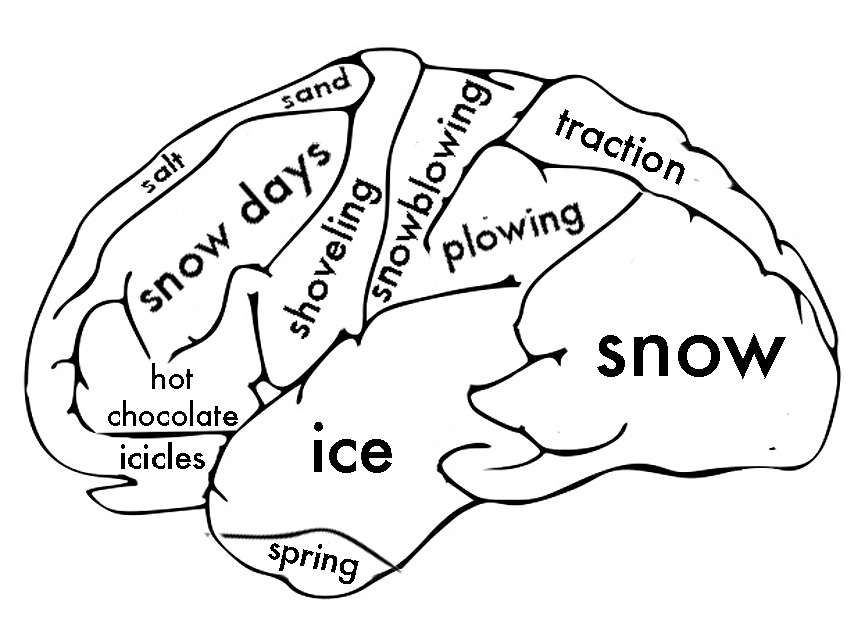

I picture one of those drawings of a head separated into different areas, lobes and such, that shows what a brain is thinking about. That’s how I described it to my sisters Friday night in the city. Up here in the country, about 80% of our brains are devoted to one thing: SNOW. I talked about how deep it is; how hard it is to walk out to the compost without cracking through sharp crust and sinking up to your knees; the kids sledding in the driveway and moaning when the plow guy comes; cross country skiing, the great season we’ve been having on the Lake and out at Fahnestock; how any energy left goes to shoveling off the flat roof, the front door and deck long abandoned to the elements; the glory and warning of icicles; and the Snow Days, having to let go of any concept of Schedule. Then I couldn’t think of anything else to say.

The next morning, Saturday, I’m on my way to Fahnestock Winter Park, a little more caffeine than usual in my bloodstream due to three hours of sleep the night before, following the worst-ever after-midnight traffic back from the city. Snow turns to rain and I have to pull over and scrape off the ice forming on the windshield, but it doesn’t register as a warning. So perhaps a little attention deficit, cruising out to a morning ski, “Reeling in the Years” accompanying me on the radio.

I have to come out of the closet here and say that I love this weather. I do my best to participate in the standard wintertime whining that makes up the grist and jist of converstation among driveway and supermarket acquaintances, even those who share the bond of sports. This year, even the cliches are worn through, and all it takes now is a shared glance, up and slightly northward, to register the absurding of our latest downfall. But I can’t, or won’t, hide the fact that I love the winter, I love being able to ski out the door and onto the lake across the street, Nordic and shoveling keeping me in shape, raising my mood and getting me out onto the white with the bald eagles. I am as excited as the kids about the Snow Days, the thrill of which must be deep-ingrained from my Midwest childhood. Even though it means another unplanned day stuck at home with the kids. It’s a lesson in Letting Go. I am one with the winter, and this morning’s drive to skate ski the groomed trails at Fahnestock is upside plenty.

Now we reach the moment, going around a turn somewhere on White Pond Road, where Letting Go becomes the lesson of my four new tires and

four-wheel drive, my forward motion suddenly translated by black ice

into sideways spinning. Either that or the scenery’s slipping, as

Bob Hope says to Bing Crosby in one of their Road

movies. By the time it occurs to me, it’s too

late. Time slows down but that doesn’t help—this is a spin, tap

the brakes? steer into the skid? Action has no effect but my mind

can easily calculate the endpoint, and I know I’m going to hit whatever

is on the other side, 180-degrees and more around the circle, and here

it comes now, the breathed expletive and the big OOF of contact.

A big bounce backwards, the inquiring glance from inside a passing car

a second shy of my trajectory.

four-wheel drive, my forward motion suddenly translated by black ice

into sideways spinning. Either that or the scenery’s slipping, as

Bob Hope says to Bing Crosby in one of their Road

movies. By the time it occurs to me, it’s too

late. Time slows down but that doesn’t help—this is a spin, tap

the brakes? steer into the skid? Action has no effect but my mind

can easily calculate the endpoint, and I know I’m going to hit whatever

is on the other side, 180-degrees and more around the circle, and here

it comes now, the breathed expletive and the big OOF of contact.

A big bounce backwards, the inquiring glance from inside a passing car

a second shy of my trajectory.No airbag. I can back out. And forward. No noise. The frozen precip that tooketh away my traction also gaveth me back the best cushion possible: a five-foot snow bank that I bounce off harmlessly. Hazard lights, a walk-around, can’t even find a scratch.

I kept going, was shaky on my skis, nervous around the fast turns, and drove home via the highways. Exhausted, it came over me how lucky I was, the worse ways this could have turned out…I won’t go into it. But boy was I lucky. From our repeated deposits into the snow-bank, I made a one-time withdrawal of safety.

A few hours later, still under freezing rain, my wife tells me she barely held on to the turn from Rt. 55 into traffic on 22 near the village. But that’s not why she’s calling. On the radio when it happened? “Dirty Work.” More Steely Dan, and from the same album: Can't Buy A Thrill.

Somewhere on White Pond Road there is a smashed mailbox flattened into the snow; I think that was me, but it’s also possible that a month of snowplows beat me to it. If it’s yours, and you know who you are, rest assured you will hear from me and recover the cost of a new mailbox. Your snow bank saved me. What could have been an accident--at best a hassle, at worst life-altering–turned instead into a bumper-car ride. Message received, no damage done.

Are you reeling in the years?

Nature’s Fingerprints:

New Photography by Norman McGrath

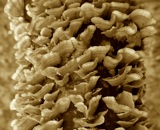

Norman McGrath is one of the country’s best known architectural photographers;

his book Photographing Buildings Inside and Out is considered the standard on

the subject. He is also an avid nature photographer with his definitive,

large-scale panoramas of the Great Swamp. For his new exhibition at Front

Street

Gallery, he has zoomed in on the unusual natural phenomenon of spore

prints—the unique patterns made by spores when they drop from mushrooms

overnight. McGrath brings his vision, and unsurpassed technical

expertise with high resolution media, to record a delicate, fragile and

temporary world.

Street

Gallery, he has zoomed in on the unusual natural phenomenon of spore

prints—the unique patterns made by spores when they drop from mushrooms

overnight. McGrath brings his vision, and unsurpassed technical

expertise with high resolution media, to record a delicate, fragile and

temporary world. High resolution images invite us into a place that is rarely seen: millions of microscopic spores dropped into fractal patterns that echo the complex structure of the mushroom. Look closely and you’ll find imperfections, trails left by tiny invisible creatures moving left among the spores.

These images are both natural and otherworldly. McGrath’s microcosms look macrocosmic: they could be nebula or aurora borealis, aerial photographs of a

bizarre landscape. Yet all of these samples come from within walking distance of McGrath’s Patterson, NY, home. Born in London, McGrath was brought up in Ireland, and took a degree in Engineering at Trinity College Dublin. He worked as a structural engineer after coming to New York, and later made the switch to architectural photography. The Great Swamp is now his favorite subject--he has been documenting it for the last twenty years.

Mycologists for years have used spore prints as a means of identifying species; Norman McGrath is discovering in them beautiful landscapes that lie somewhere between natural science and abstract art. Throughout folklore, mushrooms have been associated with magic, and these prints aptly demonstrate the magical qualities of large format photography.

Hallowed Lands October 8 2010

What's the use of a fine house if you haven't got a tolerable planet to put it on?

--Henry Thoreau

When I chatted with Louis Pescatore about his new farm stand on Grape Hollow Road up from Whaley Lake, I failed to ask him an obvious question. The signs on Route 292 read “Grape Hallow Farm Stand”—was that “Hallow” a misprint, the misunderstanding of a first-generation American, or was it intended?

There are wild grapes and apples up on Grape Hollow; I run and bike there, it’s beautiful and open, so I admit a personal interest in the fate of the landscape. Celina Davis lived in an old farmhouse overlooking a stream and small dam; I’d met her years ago pushing my daughter’s baby jogger. I knew she’d moved and sold her several-hundred acres.

I assumed that Mr. Pescatore, her neighbor on Depot Hill and the new owner, would knock down that old house first thing. Instead, he’s renovating. Has been for years. During that time, I’ve watched for other signs of development. Brush was cleared, a garage was built, pipes for perc-tests sprouted. But instead of the latest Ridgecrest MansionView Estates, I’ve been pleasantly surprised to see a barn rise, a farm with rough-hewn fenceposts, pastures, and 30 head of cattle with a rich future as grass-fed beef. It immediately struck me as sensible, and a sign of the times.

Hollow comes from the same root as Hole: empty. Hallow is from Whole, and related to Holy, Heal and Hello (from “may you be hale”). Grape hallow, then, could mean to consecrate our favorite vine, and maybe that’s how an organic farmstand looks at other fruits and vegetables too.

“We irrigate by gravity from the stream, and because of the beaver dams, the water is high, rich, and productive. I used to worry the beavers were encroaching, but now I see they’re helping.” He laughs, “And I got my kids to do the work.”

Lou’s daughter, Jessica, a makeup artist in the city, and her boyfriend Jhonny Zapata, drive up from Queens every Saturday at 5AM to work the stand. “My dad called and said how’d you like to sell vegetables. I said yes. I’m surprised how much money you can make in vegetables.” Meeting neighbors and making friends seems as much a part of it, and they give away plenty as well. Jessica and Jhonny have the bright eyes of city kids discovering the beauty and warmth of community up here. They plan is to move into Celina’s old house when they’re ready to have kids.

But other neighbors are worried. The property is mostly in Beekman, and there is talk he could put 30 houses on the land. The economy put the brakes on that, but taxes keep the pressure on to develop.

Louis called the farm’s Agricultural Use Exemption “a double benefit.” A local farm for us, a tax break for him. Do you have plans to build now? “No. Once we put the property under the exemption, now I can just live. I’m not under pressure to build financially, or even mentally—especially now that I can see my kids here.”

Louis grew up on a farm in Avellino, Italy, near Pompeii. “We are the only tribe,” he told me, “to defeat the Romans.” Now it’s better known as the hometown of the fictional Soprano family. When he bought his first farm in Patterson, his wife cried, afraid they were going back to the hard farming life they left behind. That was not her American Dream.

This farming is different. “If I do some building, if the economy comes back, I will do something like a cluster of four or five houses. I am actually glad that the economy has changed. It has made things much simpler for me. My engineers had plans to go into the mountains with roads, putting houses on top, and I didn’t realize till later that this was not the thing to do. Leave them alone, pristine as they are. For me to leave that to my kids, my grandchildren--for them to say, my father did this, that is everything.”

It’s not the first time I’ve heard someone say they are glad for the slowdown--not for the economic pain, but for the chance to take a breath and get back to basics. A small farm that produces food and friends is more attractive than a big loan, no matter how low the mortgage. Perhaps the tide has turned. The Hollow may not remain whole, but a thriving farm is a healthy sign.

Zipping at Hunter: a reminder of joy June 30, 2010

There is a wire in my backyard strung between two trees. Grab the trolly, step off a small platform nailed up at chin height, and you fly down the wire, grazing over rocks and dirt till you hit the birch opposite feet first, hopefully. The brand name of this cheap toy is Fun Ride, and it is--ride it and you will be happier at the other end, guaranteed. In that little moment of intense experience, you are a kid again, doing something silly and thrilling and risky. Your mind is stunned and you actually reinhabit your body, breathing life into a core self which looks a lot like you, only younger. All that from wire and gravity? Grow up.

Bradd Morse of Canopy Tours grew up building ziplines, and right now he’s playing in the woods at 4000 feet on top of Hunter Mountain. What he’s got planned is the funnest ride ever—the longest, fastest and highest zipline tour in North America. It will start right here, stepping off this cliff and soaring the entire valley at hawk-height.

Historically, ziplines were used by mining companies to haul material out of the mountains. Botanists in Costa Rica used them to study the rain forest canopy, and that’s where zipline tourism began in the 1990s. Costa Rica still leads the world in ziplining, with over 350 running, a billion dollar business. The US is starting to catch on. Zips are a relatively cheap and green way to add an extreme adventure to a tourist destination. Once it’s rigged, all you need is gravity and guides. At least 24 new zipline tours are opening in the US this year alone; Hunter Mountain is the first world-class zipline in the New York area.

The tour starts at the Adventure Tower, right outside the lodge. It’s an obstacle course that rises 60 feet in the air. Bradd gestures up, “This isn’t a kiddie ride, it’s all metal and wood.” Looking up at the Tower, I felt a mixture of thrill and fear. The closer I got, the better I could imagine the height, the more fear got the upper hand. Fear used that upper hand to grab me by the throat, and I choked. My foot refused to take a step. I chickened out, and it didn’t help watching a 9-year-old girl and a chubby middle-schooler bravely work their way through the ropes. Bradd’s out there encouraging everyone, especially the kids. “You can do it!” he says, and they did.

Bradd let us try some of the smaller zips that are already up, and pushing off into the air, flying between the branches over a lovely creek and canyon was a rush. But then he drove us to the top in his modified moon rover, up trails you ski down at Hunter. He points across the mountains, “See that cut in the woods across the valley? It’s a 2.5 mile hike across the valley, 3500 feet as the crow flies. That’s where the other tower goes.”

He’ll have teams hauling tons of cable across the valley through uncut, pathless forest. “The bottom of that hill is the closest we can get with ATVs. From there up to the tower, that’s a 50 minute hike and you have to carry all your tools in. You get up there and it’s like—oops I forgot my hammer…and it’s another hike down.”

Building a zipline into a natural environment is more art than science, and even though they are an experienced team working at a huge scale, there’s a certain part of the design they have to make up as they go along. “How do you get a cable across there? How do you know the exact height? How fast will it be? We don’t know. I am good at this, but ultimately you just have to ride.”

Morse,

has been building ziplines for 27 years, dividing his time

between resort destination zips in Jamaica and New Hampshire. “This is

not an ‘amusement’ park,” he says, with big quotes, “this is a real

adventure. Look at the waiver we make you sign! We like

being able to say, ‘We cannot guarantee your personal safely.’

That’s why people come and pay. That’s the difference between

this and a video game. There’s nothing soft up

there.”

Morse,

has been building ziplines for 27 years, dividing his time

between resort destination zips in Jamaica and New Hampshire. “This is

not an ‘amusement’ park,” he says, with big quotes, “this is a real

adventure. Look at the waiver we make you sign! We like

being able to say, ‘We cannot guarantee your personal safely.’

That’s why people come and pay. That’s the difference between

this and a video game. There’s nothing soft up

there.” But it is safe. “What we really sell is called ‘Perception of Risk.’ In fact we are all about safety. Unless you physically unbuckle yourself there is no danger. The weakest point in the harness line is 5000 pound test, you could hang your car from it. The aircraft grade 25,000 pound test cable does not break. That is a myth. And every bolt is inspected every week. So you are safe, but you may not feel safe.”

Most tours start with an easy ride to get used to it, but at Hunter you’ll start with the longest and highest ride. You’ll get goggles against hitting bugs at 50 mph., 600 feet above the forest, taking a raptor’s path to the other side. “I know there will be people who get up to the top and look over the cliff and say there is no way I’m going off that,” says Morse. “They’ve paid their money, and learned all about it, but they won’t be able to take that first step.” He seems to like the idea—that’s the edge he’s looking for.

Morse expects to finish the Mountain Top Tour early in the fall. Ultimately, there’s only one way to test it, and that’s to ride it, to take that big first step. That’s Morse’s job. “I build it, and I have to ride it. I’ve been doing this a long time, and that’s one thrill I still get: that first step over the cliff.” It’s his Fun Ride, and he gets to try it first.

The Signs to Holmes - the story of the comet May 28, 2010

How did I get here?

--Talking Heads, “Once in a Lifetime”

Moving from 01002, my hometown in Massachesetts, to 10012, downtown New York City, seemed natural enough. You hardly have to change the digits. My grandparents met in NYC and so did my parents. As it turned out, I found a wife there too. But 12531 I never would have predicted.

We’d been coming to our house by the lake, for weekends and weeks, religiously for 8 years. We loved being here, working and playing around the house, so the idea of moving was always rattling around. and couldn’t have come from out of the blue. But the actual decision seemed to. I’m interested in that moment when we realized that we really might do this, and practical reality started creeping in. The time we starting thinking seriously about How and When, and what it would mean for the kids. How did we get here?

We gave up our NYC apartment in June 2008. Come September, that’s my daughter running down the driveway to catch the bus that will take her away, fill her with snacks and learning, and drop her back off again seven hours later. (For this all we have to do is pay our taxes.) But it was on October 23, 2007, that the first real thought of moving came to me.

I

know the date because I keep a journal, since I got my first real

computer 15 years ago. It’s all in one huge Word.doc file,

hundreds of pages by now. My handwriting is unreadable and memory

isn’t what it once was, so having this big searchable text database of

my past is very useful. I can look up when the kids started

talking, or how long I was on antibiotics that last time I had

Lyme. In this case, I find that in Oct. 2007, I write about

“cashing out” of the city, and, a few days later, I mention calling my

sisters and parents for their opinions about moving up to Holmes.

They seem to think it’s a good idea, or they’re astute enough to give

me the confirmation I’m looking for.

I

know the date because I keep a journal, since I got my first real

computer 15 years ago. It’s all in one huge Word.doc file,

hundreds of pages by now. My handwriting is unreadable and memory

isn’t what it once was, so having this big searchable text database of

my past is very useful. I can look up when the kids started

talking, or how long I was on antibiotics that last time I had

Lyme. In this case, I find that in Oct. 2007, I write about

“cashing out” of the city, and, a few days later, I mention calling my

sisters and parents for their opinions about moving up to Holmes.

They seem to think it’s a good idea, or they’re astute enough to give

me the confirmation I’m looking for.Once you get to the point of asking, a decision can come fast, and you’ll realize you were more ready for it than you thought. Especially with the big questions, you discover that you already had an answer, if not in mind, then in heart, and as soon as you are ready to look, you find you knew where things were heading all along.

Big decisions rest heavy, and looking for more support, I also threw the coins of the I Ching, the ancient Chinese book of divination--or fortune-telling, if you like--which I’ve consulted occasionally over the years at important times. I once asked the I Ching about a Final Four basketball game and it came up REVOLUTION, which I took to mean UPSET--the year Villanova beat Georgetown for the championship.

This time the I Ching came up MODESTY: Modesty creates success. It is the law of heaven to make fullness empty and to make full what is Modest. This was easy to read: it’s a good time to get out of the crowded city, which had reached its economic fullness, and relocate to a town modestly named Holmes. Thus the superior man reduces that which is too much (our rent). And augments that which is too little (our living space). A good sign.

My journal also shows that I was pondering something that was happening in the sky. During the course of 24 hours around October 24-25, 2007, a tiny and little-known comet suddenly exploded to more than a million times its original size and brightness. It went from being visible only in large telescopes to appearing as a large star. From being about 2 miles wide to the size of the Earth. And it was still going. At its brightest, it was easily seen with the naked eye, a blurry smudge half the size of the full moon. By November 9, 2007, the comet had dispersed to an area bigger than the sun, making it the largest object in the solar system.

Weekends under the stars had rekindled my interest in astronomy, and this comet was one of the strangest events in my lifetime, like seeing a total solar ecplise or the Leonid meteor shower of 2002. I’d had a telescope back in 7th grade and seeing Jupiter’s moons and Saturn’s rings directly though a tube in my hands had been profound to me. The big event back then was supposed to be Comet Kohoutek, hyped as “the comet of the century,” bright enough to cast a shadow. I remember walking down the hill to our neighbors for a view over the southwest, and seeing nothing. Kohoutek turned out to be a dud. I let my subscription to Astronomy magazine lapse and started getting National Lampoon.

Now I wondered where this comet was heading. I was looking for it most nights, showing it to friends, taking the kids outside to see it through binoculars. What would happen if it kept expanding till it reached our atmosphere? Why isn’t this huge new light in the heavens front-page news? No one else seemed to be paying attention.

The comet eventually faded, but not before it hit me. Somewhere in there, while I was struggling over my City-or-Country decision, asking questions and searching for signs, I realized something I knew but hadn’t taken in: the name of this comet. The invisible speck in the sky that had become a big blurry ball hanging over our yard these nights and days? Named after the man who first discovered it in 1892, Edwin Holmes. Comet Holmes.

OK, thanks. Got it now. We’ll move.

A

month before the armistice in 1918, Major Fahnestock died in France,

felled by pneumonia treating in soldiers at the front lines--pneumonia

caused by the Spanish Flu, that killed more people than the war.

He was 45 years old, and the wealthiest American to die in World War

One.

A

month before the armistice in 1918, Major Fahnestock died in France,

felled by pneumonia treating in soldiers at the front lines--pneumonia

caused by the Spanish Flu, that killed more people than the war.

He was 45 years old, and the wealthiest American to die in World War

One.

I

encountered Thoreau, like most kids, in high school, when we were

required to read a section of Walden and his essay Civil Disobedience.

These were taught as lessons in the American values of self-reliance

and integrity—but he was more subversive than that. Now I read

him as the American forefather of the sturdier parts of the New Age and

self-improvement movements: he read and wrote about the Bhagavad Gita

in the 1840s. He studied books and nature with no discrimination.

I

encountered Thoreau, like most kids, in high school, when we were

required to read a section of Walden and his essay Civil Disobedience.

These were taught as lessons in the American values of self-reliance

and integrity—but he was more subversive than that. Now I read

him as the American forefather of the sturdier parts of the New Age and

self-improvement movements: he read and wrote about the Bhagavad Gita

in the 1840s. He studied books and nature with no discrimination. In

his day, his name was pronounced “thorough,” and he was nothing

but. In the patterns of frost melting out of the mud along steep

railroad embankments, for example, he found an endlessly fascinating

object of study. Over three pages in Walden he reads the thawing

clay and finds in it the structures of leaves, the quantum unit, you

could say, of vegetative life. “The whole tree is but one leaf, and

rivers are still vaster leaves whose pulp in the intervening earth, and

towns and cities are the ova of insects in their axils.” In what we

would walk by he finds, “this one hillside illustrated the principles

of all the operations of Nature. The Maker of this earth but

patented a leaf.”

In

his day, his name was pronounced “thorough,” and he was nothing

but. In the patterns of frost melting out of the mud along steep

railroad embankments, for example, he found an endlessly fascinating

object of study. Over three pages in Walden he reads the thawing

clay and finds in it the structures of leaves, the quantum unit, you

could say, of vegetative life. “The whole tree is but one leaf, and

rivers are still vaster leaves whose pulp in the intervening earth, and

towns and cities are the ova of insects in their axils.” In what we

would walk by he finds, “this one hillside illustrated the principles

of all the operations of Nature. The Maker of this earth but

patented a leaf.”  Last

Sunday, before the rain started, I was out on ice skates and ski poles

bumping over the grey ice, looking for smooth spots to try a few

turns. Some beavers had been busy on the near shore, fresh

teeth-marks in a couple of recently felled trees. A pair of

fisherman were barely in visible a mile up the lake to the north, and I

could hear but not see a snowmobile. Ideal conditions? Far

from it. But any chance I have to stand alone in the middle of

nowhere, I’ll take it.

Last

Sunday, before the rain started, I was out on ice skates and ski poles

bumping over the grey ice, looking for smooth spots to try a few

turns. Some beavers had been busy on the near shore, fresh

teeth-marks in a couple of recently felled trees. A pair of

fisherman were barely in visible a mile up the lake to the north, and I

could hear but not see a snowmobile. Ideal conditions? Far

from it. But any chance I have to stand alone in the middle of

nowhere, I’ll take it. It’s

surreal and beautiful in a winter squall, snow and ice and sky blended

to the same uniform grey with no horizon, a muffling cocoon that moves

along with you, the wind visible in a blur of sideways flakes.

You can always follow your tracks back. Afterwards, the blown

powder resolves into dunes, reiterating forms we’ve seen in the canyons

of Southeast Utah and the sandbars in Cape Cod.

It’s

surreal and beautiful in a winter squall, snow and ice and sky blended

to the same uniform grey with no horizon, a muffling cocoon that moves

along with you, the wind visible in a blur of sideways flakes.

You can always follow your tracks back. Afterwards, the blown

powder resolves into dunes, reiterating forms we’ve seen in the canyons

of Southeast Utah and the sandbars in Cape Cod.