Before that fourth wave hit, it never occurred to me that this was possible: to be alone in ten-foot seas over a reef I don’t know how deep. I come up coughing and disoriented in the foam, no flotation and no one in sight. Torn from my hands underwater, my windsurfer board and sail, the ride that got me out here, is now flipping away like a leaf downwind 30 yards ahead. Buried by the next, and already exhausted by the g-forced subwave turmoil, I know I’m in trouble. Today is my birthday, which would add irony to the tragedy.

Zoom out, and the bobbing head of a solo sailor soon disappears amid

the whitecaps and swells, and all you see is the three-mile postcard

smile of perfect beach that encloses Cabarete Bay.

Zoom out, and the bobbing head of a solo sailor soon disappears amid

the whitecaps and swells, and all you see is the three-mile postcard

smile of perfect beach that encloses Cabarete Bay. On the north coast of the Dominican Republic, the village of Cabarete is like I imagine a California surf town in the sixties. It’s been found by the fair and the fit (the Fitnazis, if you will) and big changes are coming. For now the main street is not pedestrian friendly and the inland poverty not well hidden. But all is well for we ocean-obsessed and water-minded who only face the sea. The side-shore tradewinds blow up almost every afternoon, and deep outer coral reefs pile up such waves as wave sailors dream on. German and Dutch windsurfers discovered Cabarete in the 80s; now it’s an international destination for boarders, kiters, SUPers and wavers of every stripe.

In Cape Cod, I’m one of the best sailors in our part of the bay--but trust me, everyone at Cabarete is better than you. The accents of the pros around the bar speak of charters from Schiphol and Charles de Gaulle. For us, this is the Cheap Caribbean, D.R., a 3-hour kid-friendly nonstop from Newark, 15 minutes from an international airport called POP. Lest you forget, we’re standing on the same island as post-earthquake Haiti, 70 miles up the beach to the left. Hispanola is the second-largest and most populous island in the Caribbean, where Columbus ended up after discovering America. He thought it was Japan.

We had spent a day here on a previous DR trip a couple of years ago and loved it, and this time round decided to decamp the entire week here. We rent our gear at Vela Windsurfing, a US-owned company that has been in Cabarete for 20 years, though it’s almost a mile beach walk from our rented condo. Vela's stretch of sand is a particolored hang-out of beach chairs, volleyball, a cafÈ, boutique and bar--plus a wet-dream smorgasbord of new boards and sails, every size and color rigged and ready to go. The staff of tanned Euros bring a seriously Euro lassai-faire attitude: grab what you like, swap it out whenever, take care of yourself, ask for help, break it and pay for it.

Late-winter Cabarete is not easy conditions. Vela’s brochure recommends advanced-intermediate abilities--that’s me--and explicitly discourages beginners because of the waves and chop. I’ve sailed for many years, but mostly on the relative flat water and consistant winds of Lewis Bay, and I can tell right away that this is a different game. The big rollers I’m not used to. For the first five days I sail inside the bay, turning back at the edge of the bigger swells that mark the start of the reef. For five days I watch stronger sailors buzz past on their small boards and big sails, disappearing out a mile to jump the waves. I can sail, but I feel exhausted and overmatched. “I can handle the wind but not the waves” becomes my story, the mantra of my disappointment. I’ve sailed the challenge of Cabarete, but barely.

But today is Monday, my birthday, and our last full day here. So along with whatever mid-life crisis forces are operating below the surface, there are two voices in my head as I limp over to Vela this morning. One voice is the sailors who’d told me it’s not so hard to sneak through the east reef to the open ocean where the swells aren’t so bad. The other voice is what my wife Julie always says: You never regret trying something, but you may regret not trying. The limp is from a huge blister on my left foot, but I’ll get to that later. No day but today.

(Julie’s limping too. Her knee: coming in fast her first day, riding the shore break, her long skeg hit the sand, board stopped and she flew, falling with her leg between the mast and the board. The walking wounded of a middle-aged "extreme" vacation.)

I grab a 5.3 sail and a 112 board, the smallest I’ve tried, and walk out through the shore break. The family, camped out with beach chairs and umbrellas, is watching. Molly, 10, has my camera: I beach start, reach out, turn back and come in close for a jibe before the lens. Then I head straight out, disappearing into the waves. Molly shoots it all. I see her photos later and she did a great job: I’m the photographer in the family and the least documented. How different these pictures would look had they been the last.

Beyond their sight, I keep going, faithfully, into the rising swells. Holding on and hoping, picking my way through the mountains of water, but with no sign of clear seas ahead, just more swells. And now worse: big waves starting to break over the reef. I’m tense and not sailing well. Tiptoing through sleeping giants, I know as soon as I trip over one they’ll all start to roar. I’ve gone too far looking for perfect Cabarate conditions, and already it’s time to cut my loses; when I resign and start to jibe around, I know I’m going down.

Water-starting (using the sail and the wind to pull yourself out of the water and onto the board) is tough as the swells lift me in and out of the power of the wind. I get going a few times, but am quickly overpowered. Small boards are designed to be stable when planing, balance can be hopeless otherwise. The wind has come up and the surf rushing diagonally keeps knocking me off, catapulting me from the board. I keep trying to get going but my strength is gone. There will be no satisfying last-day sail. Just like that: I’ve come too far in my hunt, and somehow, failure is not only an option, it’s inevitable.

Now I just want out. I just want to manage to find some way to sail back in. I don’t care about the Walk of Shame, of sailors who end up downwind and have to drag their rigs and sorry asses through the crowded beach back to Vela. Previous to this morning that had been my big worry. Imagine.

Meanwhile, all this time in the water not sailing and I have managed to drift over the main reef. Before I know it waves ten feet high are rolling up and breaking over me. Now I’m clinging to the board, waterblind and wondering what comes next. A succession of waves deliver a left, a right and an uppercut, and I’m underwater with the rig pulled out of my hands. I had not known or imagined the ocean’s power here, despite a lifetime of summers at the Cape. Or I had denied it in hopes of being able to sail Cabarete with the big boys and big girls.

Later everyone asked about sharks. They never crossed my mind.

In the instant, no board and no flotation, I know where I am and what it means. My pride is gone and my instinct is to scream for help, and I imagine the unhinged sound of it--the indignation and helplessess my fright would not restrain. But I don’t hear it, or won’t, because the scream stops in my throat. I can see that there is no one here to hear me. A few sails on the far horizon but nothing in reach of the strength of my voice.

How is this possible? On windy days the Caberete sky is glittered with kites and sails, streams of kiters and sailors heading out and back along the same paths and parallel tacks, making way for each other. The thought is buried in the next wave and the next, and now I’m swimming for my life. With no one around, reaching my rig I know is my one hope. Surviving depends on this: how fast a loose sail and board will blow away before waves and 30-knot winds, and how fast I can swim.

Exhausted and struggling, there is no life flashing before my eyes, perhaps a milisecond of insight into what my blindness has brought me to. I am angry at this sudden seriousness. In the purity of the moment I’m not here, I am watching myself from above. I see myself immersed in the River of Life which, it turns out, is the ocean in flood. All of your games, your ego and selfishness, laziness and horniness are swept away. Whatever crises you are chasing or running away from, you have put yourself here and now you have to get out.

The water walls piling up out of nowhere are each bigger than anything I’ve been under. The worst part of the reef on a bad day is why there is no one here. From the troughs of the waves there is nothing but sky, water and the racket of the wind. Coming up coughing, at least I can see my board, 100 feet away. I hold my breath against the waves and swim.

I’m a strong-enough swimmer, a Pisces damn it, and I grew up here. I seem to be going fast enough to reach it, but I won’t allow myself optimism till I have the board in hand.

My worst level of empty fear releases into a semblance of reality as I reach the rig. My grip on the board is now tight and determined, adrenalized by knowing what that release would mean. And it is here, holding on through the blue-green waves, that I see, rising on the next swell and looking downhill from wave-top, another sailor 50 yards on who seems in the same straits: crumpled, unsailing, adrift and hanging on.

We kick and swim our boards together and when we’re close enough he yells his mast is broken. Over the waves and under their threat, we fall into conversation with surprising normality, like two guys gazing to the water from the beach. His carbon-fiber mast snapped, he thought, not by catching on the reef below, but by the strength of a breaking wave. He wears a black helmet and is clearly a more experienced sailor, the kind who takes his every vacation amid the airs of different ports--Hattaras, Aruba, the Gorge. He’s been coming here for years. Can’t we just swim and drift in? I ask. He doesn’t think so. A current before the shore, he says. We try towing but I’m helpless at hanging on. Then he suggests that one of us take my rig (meaning him) and sail in to Vela for help. The Vela instructors will rush out with a big board to pull me in. I’ll stay and hold on to his broken rig, try to save his equipment, maybe a thousand dollars’ worth new.

He’s more stuck than I am, but he’s got an excuse--his mast is broken. I’m just exhausted and frightened. Alone maybe I would have drifted and rested and tried again when I was clear of the reef and breakers. But I trust him and agree. In the water, we exchange almost identical rigs. I feel a twinge about electing to be suddenly alone again, but it makes sense, he’s the man for the job. He reassures me we’re through the worst of the waves, then waterstarts with some struggle and is gone, “Back in two minutes,” he yells, turning over his shoulder. Well, ten or fifteen at least, I think. But the craziness is going to be over soon.

OK maybe 20 minutes--but soon there’ll be a mast coming over the bobbing horizon and the game will be over. Stay cool. Half and hour later I’m still scanning, still swimming from the breakers…and how did I know this would happen? Whatever “this” is. I’m swearing under my breath, and soon over it: what the f--, where the hell are they? Where’s the dude and where’s Vela? I could have dropped your sail and done fine paddling the board in, instead I’m dragging dead weight, trying to save your gear. And you leave me to drift? My panic is up against anger.

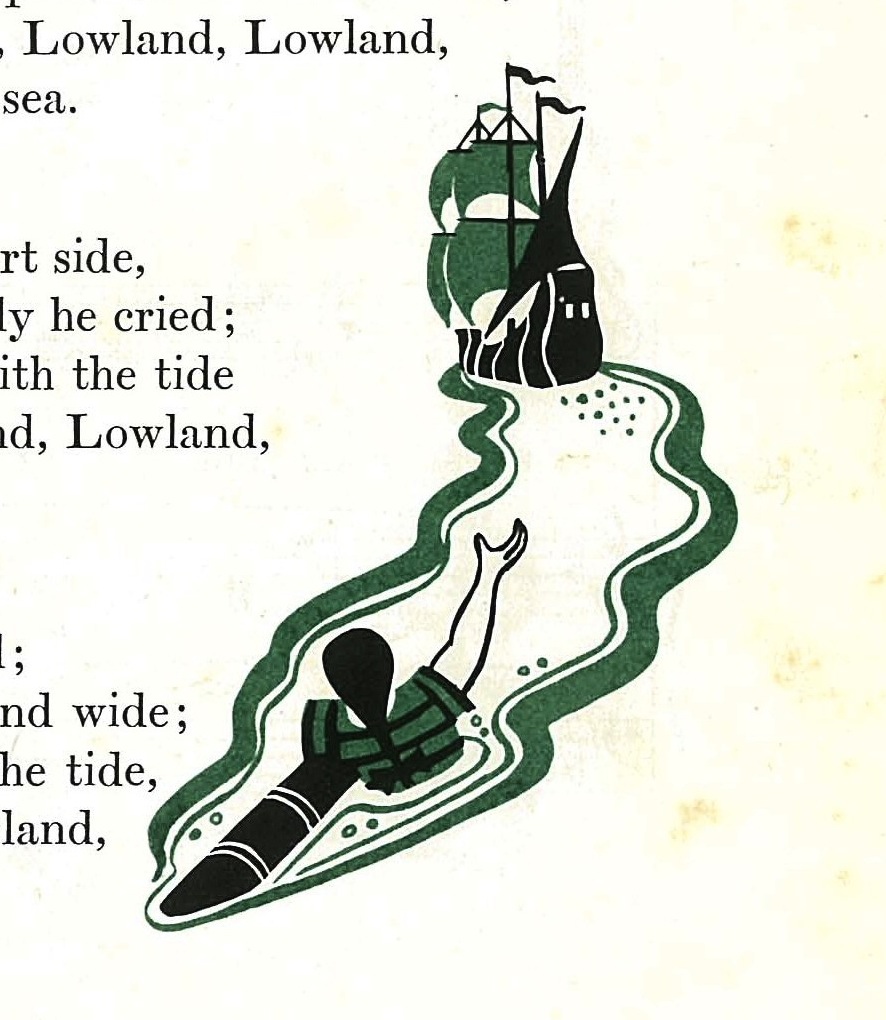

The Golden Vanity

When I was little my father played the piano and the family sang songs around the Fireside Book of Folk Songs. One that stuck from those days was “The Golden Vanity,” which tells the story of a brave sailor who is betrayed and left to die. The ship’s captain promises him riches and the hand of his daughter to sink the enemy’s ship. But the evil captain leaves the hero to drown in “the Lowland Sea.” What impressed me most as a kid was an illustration in the songbook that has never left my mind, and maybe this is why: the young sailor adrift, holding an oar and looking with confusion as his warship sails away. Now that’s me in the picture. Was I betrayed then, left behind, lost? Looking to the empty horizon, my mind can fathom no explanation.

Meantime Helmet Guy, who it turns out is a civil attorney called Shane who lives in New Jersey and sails in Barnagat Bay, sails back in to Vela. He tells the dude there I’m out drifting with a broken mast. They scan the sea with binoculars but nobody can find me. They tell Shane they won’t send someone out when they can’t see me. They stay in their beach shack staring with their binos. Shane also notices Julie talking to them too, hears her report her husband lost, she hasn’t seen him for way too long. Shane hears but decides he doesn’t want to talk to her yet. Julie had been scanning too, sweeping the horizon with my long lens, for the sight of me coming in. I’d be easy to spot: black shorts and the bright white longsleeved rashguard with yin-yang logo that she’d bought yesterday at Laurel Eastman Kiteboarding next door, and which the family had presented me that morning in bed. I’d see these photos later too, none of them of me.

She and the kids went back to the beach chairs, and eventually Shane just grabbed a board and went back out to look for me himself. And eventually too Vela sent out their own man out, our pal Wes, the nice young Brit who set up Julie on our first day.

All this I do not know. I drift and kick and go through the possibilities: I am too far downwind and they are not looking downwind. Vela has decided I should just drift in. They have given up. Helmet Guy is pathological and never told them about me. I don’t know what to think. I am heading down the beach, away from my family, no idea what waves or current or shore break is coming. I’m sick of being alone out here, of this not making sense, and I am ready to be rescued already. I am ready for this to be over, and to commit: I will never to do this again. I will always wear a PFD. I will fully appreciate my old beloved Cape Cod flatwater.

Half a mile from shore now and out of nowhere a kiter zips by, near enough to catch me with a hard look. He tacks back closer and yells, in his indeterminate non-American accent, “Do you need help?” I scream back my mast is broken, which does not answer his question, exactly. So he yells again, and this time I say Yes, help. He immediately slips his feet from his board, drops it and lets it drift in, his torso still dangling aloft below the wires of his kite. I’ve been watching kites all week but have never been under one all powered up. The huge yellow kite blooms 60 feet over our heads as he pulls loose a line with one hand and instructs me to hook it to my harness. Before I can we are jerked apart by waves but after more swimming I finally grab his line and hook in. I am attached to this man and his kite by a cable, and when he gyrates to lower the kite into its power range, it suddenly lifts him bodily out of the water, jerking me through the water with it. I’m still dragging the weight of the rig behind me and pulled sideways through the surf, but my head is above the ocean and that’s enough for me. We are zigging clumsily through the water, the power of the kite released in spurts, and soon we’re into the bigger waves of the shore break. One last big tumble, a chaos of wave and board and flapping sail, but that’s sand now under my two feet and I push out of it. I unhook from the kiter and muscle the rig up onto the sand. He is long-gone before I can thank him, my rescuer, down the beach looking for his board. Gracias, Senor.

I’ve landed in the blinking bright light of a blustery beach day in front of the Tangerine, a crowded all-inclusive resort (or ‘all-exclusive’ as Moll was calling it) at the opposite end of the bay from Vela. I’ve hauled up their rig and saved my ass. Soccer goals and chaise lounges are scattered at angles, browning tourist flesh in the off-yellow light of late afternoon. I disconnect the broken rig, drop it in the sand and start back, hoisting the board over my head.

I can’t imagine what Julie and the kids are thinking. They have no idea where I am or what has happened. Whatever I’ve been through, I know it’s been worse for them: at least I knew where I was; they still don’t. Waves are scary but not knowing would have torn me up.

Looking around, it’s a different day here: the wind has raged up and the light is sharper, kites and sails are whipping about on the edge of control. I can’t hear my breath in the wind. There’s a blond kid running my way, full speed hair whipping, binoculars in his hand and I focus and recognize it’s one of the Vela guys, the German kid Julie insulted by asking if he’s Dutch. He pulls up to tell me he has come to make sure I’m OK. He points to Wes, still out on the ocean searching for me, his small sail among the breakers on the reef. Yeah, I’m fine.

Now comes running up the broken-masted sailor, still in his black helmet. Trailing just behind and breathless is my daughter Molly; she is sobbing and I feel it as she comes into my arms.

“Do Mom and Joe know I’m OK?"

“Yeah, the Vela guy ran by saying they spotted you at the Tangerine. I tried to keep up but Mom stopped me and told me to bring these,” she said, handing over the water bottle and the sunscreen she was running with.

“Thanks for these, sweetie.”

“When they said they spotted you I still l didn’t know what they meant, maybe you were unconscious or had a broken leg or--”

“I’m fine. I was just drifting with my board.”

The blond guy continues on to to fetch the broken sail, and Helmet Guy takes the board from me as we make the long walk back Vela. I’m still limping hard on the big blister I acquired my first day here. It hurts like hell but acute pain is tolerable: I know it will heal eventually.

“Mom was using your camera to look for you. We were scared.”

“I was out looking too,” says Shane, “but we couldn’t find you. We couldn’t figure it out.” Maybe I should have spent more time sitting on top of the board trying to be seen over the waves, instead of down in the water resting and holding on.

Limping home: no shame. Back at last from my sail, back to our chairs and umbrellas, and Julie comes into my arms sobbing too. I’m sorry; I’m just glad you’re OK. Looking up from her hug, there’s my son Joe, age 6, meanwhile, showing no emotion. Rather, he seems distracted and impatient, barely able to keep still on his beach chair. Almost immediately he starts bugging us about how he wants to go back to Vela now to practice more windsurfing.

This morning, before my ride, Joe had announced that he was going to learn to windsurf. The wind had already come up too much for a lesson, but we agreed to a lesson tomorrow if the weather was good; meantime he could play with the simulator--a board and sail on the beach for learning the basics. Now I’m back he wants only to get back to it. Nothing makes me happier than my son wanting to learn to sail, but hold your horses, kid, Dad just got back from his Ordeal. Give me a minute. I fall back into the umbrella-ed shade. Beer will come, and chicken.

When I wake up on Tuesday morning, the floor is moving and I can still feel the waves rocking. But as we head down beach for another breakfast at Vela, Joe is unwavering in his quest for a lesson. Half an hour later, Wes, who the day before had searched for me among the waves on the reef, is getting Joe set. “I had the ride of my life out there looking for you,” he’s smiling, thanking me almost. Now he’s walking my boy through the shore break for his first lesson. Big flat board and a little one-meter sail, but it’s a great start. Joe gets going on his own and even learns a little 360-spin trick. “He kept saying, Good one, mate!” Joe announces on his return to the beach.

The first morning after we flew in I went for a long sunrise run, barefoot and blissful the length of the beach and back both ways. Next day, payback: that fine sand on my winter-white feet had given me my worst blister in a lifetime of running, big and unavoidable on the ball of my left foot. In Cabarete there is no alternative to beach walks and no combination of bandages and socks and watershoes could seal off the pain or protect it from re-opening. It stayed with me all week, raw and sandy and worse. The only time I didn’t feel it was when I was windsurfing. The surface of the board is called the “non-slip” and is basically sandpaper, so you can sail barefoot. When I got off the board each day, the pain would rush back into my foot and I’d stalk the beach with a stupid limp. Sailors at Vela were using Super Glue on their blistered fingers, but this was too big for that. I limped for a week there and for another week once I got home. The adventurous ocean had taken me elsewhere, but this near-constant pain was way-mundane: a hole in the most practical part of my foot that couldn’t begin to heal till my travels were over. Guess where my Achilles Heel turned out to be.

At the airport we run into Shane with his wife and little girl, who had been running around in the sand with Joseph a few days before. We chatted before our flight. “You picked the worst time on the gnarliest day,” was how he put it. “The waves were mast-high on the reef, logo-high where we were.” I started to tell him about sailing at the Cape, but broke off to chase my kids who were looking to turn our last pesos into junk food at the other end of the airport when the boarding call came.

June 2011 For Henry Starr