Inside Virtual Reality

(The Myth of Transparency and the Myth of Reflection)

A couple of weeks ago I spent two minutes inside a virtual

reality. I put my hand into the dataglove, the heavy,

hardwired

goggles were lowered over my head--and suddenly I was through

the

screen and into a computer-generated environment.

A checkerboard

plain surrounded by a green field stretched to a blue horizon.

When I

turned my head, I could see the rest of my computer-animated

world:

red pyramids and yellow columns, a floating grey box, a

toy car and

airplane, a balloon overhead. Responding to the movements

of my hand

inside the dataglove, my vitual hand, yellow, disembodied,

floated in

front of me. Pointing with my index finger made me

to fly to an

object. I could grab the car or the plane and move

it to a new

position. Or look up at the balloon overhead, point

to it, and fly

up, the checkerboard plain receding below me. I flew

through the

balloon into an unseen cityscape...out of the balloon, arcing

over

the more-familiar plain and back down to the solid surface

of my

virtual world.

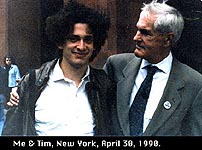

I took this trip at a press conference before a lecture and

demonstration advertised as "FROM PSYCHEDELICS TO CYBERSPACE."

The

show, April 30 at NYU's Loeb Student Center, featured Sixties

LSD guru

Dr. Timothy Leary, author and conspiracy-theorist Robert

Anton Wilson,

and the first public demonstration of Virtual Reality (VR)

technology

on the East Coast. I had been fascinated with the

concept for months,

and when I heard this road-show was coming with the real

equipment, I

made sure I got to try it.

Virtual Reality (sometimes called artificial reality or

Cyberspace) is hardware and software that puts you inside

a

computer-generated graphic world. The goggles (or

"eyephones")

position two TV monitors before your eyes, aligned to create

a 3-D

stereoscopic image. When you turn your head to "look

around," your

head movements are tracked electronically and the computer

alters the

image before your eyes accordingly. The illusion--the

experience--is

of a complete, 360-degree environment you can look around

at and move

through.

After two minutes of tooling around in VR I was pretty spaced

out. (That is the correct term.) But I felt

proud and ripe for the

future when Eric Gullichsen, President of the SENSE8 Corporation

of

Sausalito, CA, whose equipment this was, told me I was a

good pilot.

Gullichsen is a demure and clear-speaking 30- something

young man with

a scraggly beard and a very long blonde ponytail.

Recent VR systems required half-million-dollar computers to drive

their software; Eric's "Desktop Virtual Reality"

prototype is run by a

Sun Sparkstation, a $12,000 dollar computer now selling

as fast as the

top-end Macintosh, and which Eric predicts will be down

to $5000 by

the end of the year.

The dataglove gives an even

better idea of how fast this stuff is

moving out of the lab and into our lives. A year ago,

Eric's demos

used a prototype that cost $8000. Now he works with

a

"Powerglove"--made by Mattel for Nintendo.

It sells for $79.

Even with a lot of power behind it, SENSE8's VR is about as slow

and low-resolution as it can be to work at all. But

you still get a

sense of the possibilities. It's not so much that

the experience

doesn't live up to the hype: more that the experience

is hard to

connect with the amount and variety of hype.

Doing It was brief, unique, somewhat ineffable. The hope,

hysteria and hypotheses that have arisen out of the concept

of VR is

what the rest of the event at NYU was all about: several

hours of

dreams and visions, tech-talk and peptalk on what this stuff

is for

and what it will do. My two-minutes' experience aside,

you can't help

but feel Something's Up, just from the assortment of strange

characters and corporations clammoring to jump, or at least

keep an

eye, on the VR bandwagon.

Representing psychedelics at the "From Psychedelics to

Cyberspace" show was Dr. Timothy Leary, the former

Harvard Prof. and

Acid-activist, now willing to commit his career-long utopian

dreams to

this straight, labcoat technology. (The work of nerds!)

Age 70, he

comes bounding on stage, energetic and radiant, in brand-new

white

Adidas and a sharp suit sporting a "Just Say Know"

button (for sale,

$2). His ramblings have slowed, but you still have

to pay attention

to follow the playful and curious threads of his thinking.

Among many

other things, he's here to contend that 90-percent of the

engineers

and programmers creating the current personal-computer revolution

are,

like Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs (the founders of Apple

Computers),

veterans of psychedelics. That Silicon Valley is a

stone's throw from

Berkeley and the Haight, he says, is no coincidence.

Technology (of all things) is allowing Leary to speak in a new

and more accessible way about the benefits of altered consciousness.

He thinks the experience of these computer- generated realities

breaks

down the "straight" idea of a Real World or an

Absolute Reality as

much as the LSD experience did--but without the stigma of

"Drugs,"

which has always prevented Leary's theories from being taken

seriously. Instead of sounding like a chemical prophet,

he's talking

about technology and innovation and competition, like some

Lee

Iacocca-type on TV, "Working to make America great

again."

During the show, Leary was the first to demonstrate the goggles

and glove. He was strapped in by Gullichsen, then

took off, twisting

his wired head around, giggling, and squirming in his chair

as he

glanced, pointed and flew through his imaginary world.

"Whoa-ho,"

came his self-mocking laugh, "I've been here before!"

"PSYCHEDELICS TO CYBERSPACE" pulls virtual reality into

the realm

of drugs, and also into the world of Science Fiction:

"Cyberspace" is

sci-fi writer William Gibson's word for his conception of

VR. Gibson

posits the ultimate interface--what he calls being "jacked

in": a

direct link from machine wires to human nerves and brain.

In the

world revealed in his 1984 novel Neuromancer, Gibson's characters

can

jack into cyberspace--a computer-generated visually abstracted

matrix

of information--or into the live or recorded senses (the

"sensorium")

of another person.

Gibson's vision, and his role in the development of the concept

and consequences of VR, is taken very seriously; his name

comes up in

every VR speech, and the scientists talk like he's one of

the boys.

Gibson's idea of a direct interface is beginning to happen

(in work

with damaged hearing, experimenters are connecting microphones

directly to auditory nerves); current VR technology is not

direct, but

tries to make the human-computer interface transparent (that

is,

perceived as direct). The effect is to put "you"

(some part of you,

some ratio of your senses) into an artificial world that

you can

actually move through and operate within.

"Artificial Reality"--the first term used to describe

computer

and video environments--was coined by author-inventor-engineer

Myron

Krueger in the early Seventies, and is the title of his

seminal book

on the subject. Written in 1972 but not published

until a decade

later, Krueger's Artificial Reality presented all the major

concepts

guiding today's VR investigations, including the idea of

a dataglove.

Krueger, hailed by all present as the "Father of Artificial

Reality," was the first speaker. "I feel

a little like Rip Van

Winkle," he said, "except that it's the rest of

the world that's been

asleep for 20 years." A good-looking, square-jawed,

clear- eyed

American, he could be your milkman or your mayor, or your

math

teacher. He has the down-to-earth practicality of

someone who, in his

words, "knits computers," but he too talks about

science fiction's

role in real-world breakthroughs: "I don't read

as much now, but when

I was younger I read everything. I used to believe

it when someone in

this field said they hadn't read science fiction; I used

to believe

it, but I don't anymore. I don't think it's possible."

Conspicuously absent was the best known and most publicized of

the VR pioneers: Jaron Lanier, a 29-year old white

rasta and high-

school drop-out distinguished by his long dreadlocks and

his NASA

contracts. He makes the most mystical claims for VR,

which might not

be taken seriously were he not ahead of everyone in VR software

and

hardware and working for the government. Jaron (everyone

here invokes

the demi-diety on a first-name basis) sees VR having therapeutic,

ritual uses--in the way of psychotropic drugs in shamantic

tribes. A

recent Wall Street Journal article on Lanier offered these

brave but

tentative subheads: "COMPUTER SIMULATIONS MAY ONE DAY

PROVIDE SURREAL

EXPERIENCES," and, "A KIND OF ELECTRONIC LSD?".

You get a sense that Leary and Wilson are hitching their old

messages to The Next Big Thing. But, in fact, the

connections they're

making hold remarkably well. One message is that VR

does what

psychedelic drugs do. Another message is political:

how electric

communication will break down the fascist control of centrist

governments. "It was electrons," Leary says,

"that brought down the

Berlin Wall".

Politics, drugs, science fiction, philosophy, and mysticism are

just a few of the fields and factions inspiring and being inspired

by

the technology and inventors of Virtual Reality. When

consciousness

is extended by electronics, science and philosophy are in the

same room, and the

ramifications everywhere in between.

Leary, Wilson and Gullichsen each referred to VR as part of an

electronics revolution that will change television from

a passive to

an active medium--the Viewer will no longer be in the thrall

of the

broadcast monopolies, whose centralized control stems from

the current

state of TV technology (i.e., TV is cheap to receive, but

only a

government or big corporation can afford to produce and

broadcast).

That's changing, with cheap VCRs and portable cameras; with

cable, and

especially fiber-optic cable, which will increase television's

interfaces with computers. All of these new forms

(including, soon,

VR) give the individual more control and choice as to how

to use the

medium. Strictly speaking, "Television"

as a medium is visual

electronic information; your Mac is as much a TV as your

Sony.

Television will no longer be just a receiver for a centralized

broadcast medium, but one component of an interactive, computer-based

communications network.

"VR is a network like the telephone, where there is no central

point of origin of information," Jaron stated in a

recent interview in

the Whole Earth Review. "Its purpose will be

general communication

between people, not so much getting sorts of work done."

He's already

created a "Reality Built for Two" (RB2), a virtual

space in which two

people interact.

Virtual reality is like the telephone medium, which

opens a new

realm for human interaction but doesn't affect the content,

i.e., what

you talk about. The technology of VR per se has nothing

to do with

what you create or do within it. But reactions are

strong whenever you explain

the concept. Fear is common, a kind of Brave New World/1984

paranoia.

A professor I described this stuff to waxed rhapsodic about how

it signals the end of the

mind-brain duality, creating a sort of spiritual or mystical

materialism. (John Barlow has published an article

on VR called Being

in Nothingness.) Leary and Wilson look into VR and

see a

technological utopia. Others dream of its pornographic

possibilities--virtual sex-partners. A visionary-

rebel like Lanier

is drawn to mystical ends; as the Wall Street Journal observed,

"[His]

obsession with Artificial Reality seems to reflect his dissatisfaction

with conventional reality."

These are all understandable human reactions. Every new

medium

works like a mirror, reflecting back some part of ourselves.

The

telephone, in this sense, "reflects" our speech

and hearing. VR is a

mirror that reflects our entire consciousness--more than

anything specific about what VR does, these reactions reveal

us.

Marshall McLuhan addressed this phenomenon in Understanding Media

(1964), labelling it "Narcissus as Narcosis."

In the myth, Narcissus

falls in love with his own image, unaware that it is his

reflection.

He is numb or blind to an extension of himself, and remains

unaware of

the medium operating on him, in this case, a reflecting

pool. With

any new medium, we are entranced by its content--which is

an extension

or reflection of some part of ourselves--but remain numb

or blind to

the operation of the medium itself. We are able to

look through or

conceive into a mirror because it is a perfect visual technology,

it extends our sense of sight with true high-def accuracy. But

the surface

of a mirror (the place where its technology is operating) is impossible

for us to focus on

or perceive as a two-dimensional plain. Every media technology

entrances us with its content but operates in a similar blind

spot.

The thinking of McLuhan (who was dubbed "the Media Guru"

around

the same time in the Sixties when Leary was accorded guru-status

for his work with psychedelics) lurks at the edges of a

lot of the

ideas VR is inspiring. Like Gibson's, his name came

up several times;

Gullichsen quoted McLuhan--"In the future we will wear

our nervous

systems outside our bodies"--as a preface to demonstrating

his

data-goggles and glove. And Leary later gave a good

illustration of McLuhan's best-known maxim, The Medium Is

the

Message: "When Moses came down from the mountain

with the Word of God

carved into those marble tablets, let me tell you, boys

and girls,

those were not suggestions...."

McLuhan prefigured the electronic extension of consciousness more

than 25 years ago: "Having extended or translated

our central nervous

system into the electromagnetic technology, it is but a

further stage

to transfer our consciousness to the computer world as well.

Then, at

least, we shall be able to program consciousness in

such wise that it

cannot be numbed nor distracted by the Narcissus illusions

of the

entertainment world that beset mankind when he encounters

himself

extended in his own gimmickry."

All the reactions to VR (the "Narcissus illusions")

say nothing

about how this particular mirror works or why our brains

are able to

conceive into and make from this mass of electronic information

a

space that is perceived as real.

VR technology does not create "reality" in any sophisicated

way;

in fact, it works in the most unsophisticated way, revealing

our

simplest perceptual illusions. The "space"

one enters during the VR

experience is not visually sophisticated; rather it takes

advantage of

our inclination to conceive three-dimensional space out

of two

dimensions. In the West, we have been trained to see

depth in the

simplest two-dimensional drawings if the lines of perspective

are

right. We perceive depth in a line-drawing of a cube

(the classic

"optical illusion"), but this is a relatively

recent technical

development (perspective drawing is a Renaissance invention).

The

effect will not work in a society whose visual perceptions

have

not been trained in this way.

Myron Krueger: "What VR does is highlight the status

of

artificial experience which we already have lots of."

Jaron Lanier:

"The reason the whole thing works is that your brain

spends a great

deal of its efforts on making you believe that you're in

a consistent

reality in the first place. What you are able to perceive

of the

physical world is actually very fragmentary. A lot

of what your

nervous system accomplishes is covering up gaps in your

perception.

In VR this natural tendency of the brain works in our favor.

All

variety of perceptual illusions come into play to cover

up the flaws

in the technology."

Entering SENSE8's "flawed" virtual reality on April

30, 1990, was

the culmination of an exactly nine-month gestation period

whose

conception was my first encounter with the idea of electronically

extended consciousness in the real world. From then

on it was as

though I was being bombarded by the concept, and from so

many diverse

angles that it was impossible to ignore. It started

on August 1,

1989, when I read an article in the "Science"

TIMES about a device

called a teleoperated robot. The operator of the robot

moves two

mechanical arms that move, remotely, a robot's arms.

A helmet covers

the operator's head, with speakers by his ears and two small

video

monitors before his eyes--with which he "sees"

and "hears" via the

video-camera eyes and microphone ears on the robot's head.

The

technology allows delicate and dangerous work (like disarming

a bomb)

to be done from a safe distance. The term "telepresense"

has been

coined for the perceptual illusion: "The closer

you come to

duplicating the human experience, the more easily your mind

transposes

into the zone as though you were there," operators

say. "You forget

where you are."

"Telepresence" got me, and the idea that "your

mind transposes

into the zone as though you were there." This

was the first real

example I'd come upon of what McLuhan had predicted more

than 25 years

ago, the electronic extension of consciousness or electronic

direct

experience. (Like VR, telerobotics puts your consciousness

elsewhere.)

Shortly after, a young Seattle programmer friend of mine asked

if

I'd heard about Virtual Environments, and it was from him

that I first

learned of the goggles and glove and suit you could wear

to see in and

move around a computer-generated space.

The next time I encountered the idea was in the unexpected

context of an interview with Jerry Garcia in ROLLING STONE

(Nov. 30,

1989). "Have you heard about this stuff called

virtual reality?" the

lead-guitarist for the Grateful Dead asked his interviewer.

He went

on to describe the idea quite cogently, and also to connect

it with

psychedelics: "You can see where this is heading:

You're going to be

able to put on this thing and be in a completely interactive

environment...And it's going to take you places as convincingly

as any

other sensory input. These are the remnants of the

Sixties. Nobody

stopped thinking about those psychedelic experiences.

Once you've

been to some of those places, you think, 'How can I get

myself back

there again but make it a little easier on myself?'"

Then I read Neuromancer--Gibson's sci-fi novel (and I've

never liked sci-fi) which introduces and explores "Cyberspace"--and

the interview

with VR-pioneer Jaron Lanier. Reading Gibson and Lanier

at once,

I was startled by how close sci-fi and fact had become.

Appropriately, it was via ECHO, a new computer bulletin-board,

that I found out about "From Psychedelics to Cyberspace."

I'd joined

ECHO a couple of weeks before; getting a modem and entering

the world

of telecommunication transformed my computer from a typewriter

to a

tool for putting ideas online in real-time, a new medium

for

conversing with a group of unseen others, like me, typing

down the

telephone lines.

VR is the beginning of another new medium for human

communication--huge amounts of processed digital information

used to

create the bare-bones of what our brains perceive as "reality."

What's

new is that this realm of information is encountered as

experience.

The content of the telephone medium is speech; the content

of the

television medium is movies and drama and talking- heads:

with the

telephone or TV, you are aware of the inside and the outside--of

the

medium and its limits, and of the real world that surrounds

it. The

TV or telephone experience does not exist separate from

its entrancing

content (which is itself a different medium, what McLuhan

calls "the

juicy piece of meat carried by the burglar to distract the

watchdog of

the mind"). In VR, there is no such duality.

You know it's not

"real," and when the perceptual illusion works,

you are just Being

There. The content of virtual reality is not speech

or action or any

other visual or auditory medium. The content of VR

is consciousness.

This sets up a basic question about the difference between

information and experience. Information--the kind

that comes from

other people or books or movies or TV--is mediated experience.

It is

not like the Real World--the real, direct experience of

things that

surround us. VR is also information, but it is perceived

as

immediate; that is, it is not mediated or digested or translated--

it

is just "lived." If "experience is

the only teacher," it was the

experience of psychedelics that taught many people, in a

profound and

direct way, the limits of "reality." The

experience of VR can teach

that too, and many other things.

Playing a video-game or reading a book or watching TV or a movie,

there are times when you are unconscious of the medium,

when you are

immersed in its content (when "the watchdog of the

mind" is chewing

that meat). At other times you are aware of the television

or the

book's boundaries. Within a virtual reality, there

is no such losing

and regaining awareness of your state. You are aware

of its unreality

and perceive its reality at the same time and all the time.

In fact,

in VR you have a heightened awareness of perceiving reality

in an

unreal system. Your consciousness it at once the perceiver

of VR, and

its content.

All of which is thrilling to ponder. But if this stuff is

going

to develop on a mass scale, it has to get there via some

marketable,

real-world applications. Many people think VR will

be carried through

this phase by pornography, as was the case with the

VCR less than ten years ago.

Krueger and Gullichsen, guys on the practical, hands-on, I-

need-funding side, are working to come up with simple, high-concept

applications that even America's short-sighted venture capitalists

can

understand. This sets up some strange situations (since

they are

courting business partners but depend on frontmen like Leary

to bring

in the crowds and press), like when these older corporate

guys in

suits arrive en masse to check-out Gullichsen's gear.

They look like money; like their good graces could shower SENSE8

with contracts and options. They struggle with the

eyephones and the

glove. They did not grow up with TV--they are not

good pilots. Eric

is deferential and cogent and clear, trying to dispel with

his manner

any doubts his long blonde ponytail and rough beard might

cast. And

then the suits have to sit through the lecture, surrounded

by

college-age Trekkies and every stripe of New Age huckster

(a man

selling "psycho-active soda" for three dollars

a cup), and listen to

Leary and Wilson make fun of Bush, Quayle and the drug-addict

Drug

Czar.

Gullichsen does his best to talk toward the most mundane

applications: Imagine an architect showing a client

around a

"virtual" building (it's been designed but not

built). The client

wants to see how it looks with bigger windows, so the architect,

in

the virtual world, can reach over and enlarge the windows

with his

hands. Another area he talks about is education--the

Defence

Department's use of VR in fighter-pilot training is probably

the most

sophisticated form now in practical use. A related

application, the

first one we're likely to see, is in entertainment, VR video-arcade

games.

Krueger has one device that's so basic and useful, it seems

inevitable. Simply put, it allows you to use your

unencumbered hands

to do anything a mouse does--access menus, draw pictures,

move text,

etc. (Of course, this isn't VR, you don't put goggles

on and put your

head inside. But it should make Krueger rich while

he waits for the

technology of the goggles, and the 3-D imaging and computers

that run

them, to catch up to his ideas.)

Leary, not surprisingly, flies off into the future, imagining

VR

as some kind of holographic telephone. "You'll call

up your friend Joe

in Tokyo and say, Where do you want to meet today? and press

some

buttons and the two of your are strolling in Hawaii, or

meeting in a

cafe in Paris or on top of Everest, or joining Aunt Ethel

for tea in

Idaho."

Jaron Lanier seems to have the most developed ideas about how

VR

will function and where it will be relevant. He talks

about

handicapped people experiencing full-motion interaction

with other

people, and tele-operated mircorobots performing surgery

from within

the human body. But he also builds on Leary's dreams

of the

therapeutic uses of psychedelics as tools for exploring

the

unconscious mind.

"Idealistically, I might hope that VR will provide an experience

of comfort with multiple realities for a lot of people in

western

civilization, an experience which is otherwise rejected.

Most

societies on earth have some method by which people experience

life

through radically different realities at different times,

through

ritual, through different things. Western civilizations

have tended

to reject them, but because VR is a gadget, I do not think

that it

will be rejected. It's the ultimate gadget.

"It will bring back a sense of the shared mystical altered

sense

of reality that is so important in basically every other

civilization

and culture prior to big patriarchal power. I hope

that that might

lead to some sense of tolerance and understanding."

Jaron envisions

the VR experience, potentially, functioning like an Amazonian

shamantic drug ritual for the electronically re- tribalized

Global

Village.

VR is now at the Wright Brothers stage, the thing's sputtering

and popping and just barely getting off the ground--and

everyone's

trying to predict what moon-rockets will be like.

Back then, instead

of William Gibson, you had Jules Verne's sci-fi model; and

in sixty

years we did walk on the moon. But who could have

imagined any of the

mundane and earth-changing reality in between-- 747s and

People's

Express and plane-food and in-flight movies and jetlag?

Who, looking

at television in the 40s, could have predicted Watchman

TV or

palm-size video cameras or the worldwide resonance of seeing

Tiananmen

Square on CNN? And the speed of the computer revolution

is on an

altogether different scale.

If cars had progressed at the same rate, they'd cost $10 and run

for a lifetime on a tank of gas. In ten years flat

we've gone from

4000 to 4 million transistors on a thumbnail chip, and the

power is

quadrupling every two years. At this pace, science

fiction like

Neuromancer becomes a myth of the present. The technology

has

progressed faster than our ability to even imagine what

do to with it;

it's almost as though it has appeared magically and full-grown

in our

midst. The VR toys now being demonstrated barely scratch

the surface

of the brain-extending fun and games possible when creative

thinking

gets applied to this new and limitless computer power.

Hold tight:

the unimaginable future of virtual reality is only a few

years away.

16.5.90

VR Update--4/93 Since writing this VR piece in 1990, I've had a couple of other encounters with the medium. The first was in a movie theatre. I'd just seen "JFK," and a new VR machine was set up in the lobby. It cost four dollars for a two-player game in which you share the same virtual space with a competitor. The object was to shoot each other. The helmet and joystick worked better, the images moved faster and the environment was more interesting than the previous VR set I'd been in. I ran into this same double machine a few months later at a They Might Be Giants record-release party (the album had a futuristic title--"Apollo 18"). The first time I tried it, I stalked my opponent (someone I didn't know) over the geometric landscape, up and down stairs, around colorful objects, wary of the flying pterodactyl that could carry me away at any time. I could see the other person, who was green, and my own outstretched yellow gun hand before me. I was comfortable looking around and moving through the environment, and managed to win, three kills to one. The second time I went in, it as with my friend, the composer Joshua Fried, as my opponent on the machine. Before we started, it was Joshua's idea that, instead of fighting each other, we hang out in the virtual space together, and shoot at the pterodactyl as a team. This was a true insight on his part and an entirely different experience. Once inside the virtual space, I looked around for the other computer-animated character, which I knew to be Joshua. We saw each other, and moved to stand close together. (Perceiving ourselves "together," though we were in fact 15 feet apart on separate platforms, blind under helmet/goggles.) Facing each other in this silent, mutually imagined, low-resolution visual space, Joshua and I had the same instinct: to make contact. Immediately, using our gun hands, we waved to each other. Knowing it was him, somehow, was genuinely thrilling. The rest of the time we followed each other, pointing to and shooting at the flying dinosaur. Joshua remembers looking down and seeing our two pairs of feet together. The experience of Being Together "there", of actively connecting with an unrecognizable friend in an imagined place, contained a vast insight about this technology. This simplest contact, even in the most poorly defined visual space, was exciting and authentic and "felt"; it was natural and instinctual. The "game" or "entertainment" idea which keeps players competing at a distance and out of touch seemed the leftovers of an old fashioned technology, and dull and superficial by comparison. Joshua and I had been together. We'd communicated without words and without out actually seeing each other in an imagined space, a consensual illusion existing only in our brains. The tenousness of the contact heightened the reality of the connection, like touching someone in the dark. And the experience would have been the same if we'd been in different rooms or different cities or different countries. When we got out of our helmets and stepped down from our platforms, the guy running the machine said, "What are you guys-- consciencious objectors or something?"